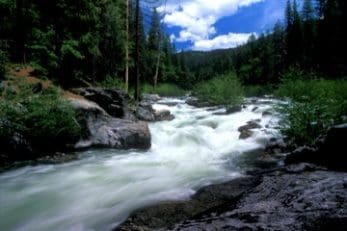

The drive on Highway 49 from Auburn to Yosemite is particularly spectacular in late May just before Memorial Day. Winding through the Sierra foothills, the road twists and turns through luxuriant shades of green punctuated by the brilliant gold of poppies and the deep purples of lupine. As one leaves the beauty of the American River canyon, one is rewarded by a succession of other canyons, each carved by a different river. After the American River with its three forks, the North, Middle and South Fork, one encounters the canyons of the Consumnes and Mokelumne Rivers. Then comes the North Fork of the Stanislaus River, the main Stanislaus River itself, the Tuolumne, and finally the Merced River, which courses through the legendary Yosemite Valley. If you can imagine your thumb as the Sierras, these rivers would be the lines on your outstretched palm, each carving its way from its origin westward toward the sea. To encounter so much natural beauty in so small a space would seem to be a timeless gift. Yet when I began boating these rivers in 1974 every one of these places was about to be destroyed by a dam.

It was already too late for a portion of the Tuolumne River, which once had a valley called Hetch Hetchy that John Muir felt was equal in its beauty and grandeur to the Yosemite Valley. When it was destroyed by what later proved to be an unnecessary reservoir, they say it broke John Muir’s heart. He died soon after. I can imagine how he felt because the next valley to be destroyed was that of the Stanislaus River, my first whitewater love, which was lost to the far more questionable New Melones Reservoir. The struggle to save the ‘Stan’, at the time the most popular whitewater river in the West, created Friends of the River and launched the river conservation movement in California. It also motivated me to establish Scott Free River Expeditions as a means of promoting river conservation. Scott Free later became Mother Lode.

As I cross the New Melones Reservoir, I notice the series of bathtub rings that scar the place where California’s once most popular whitewater river once flowed. The water this reservoir contains was intended for irrigation and yet farmers chose not to sign contracts for it. They preferred the older, cheaper water contracts and chose to install drip irrigation and drill for groundwater to avoid buying water at higher prices. Resultantly, the destruction of the Stan never served its original purpose. What a waste!

River conservationists have succeeded in preventing the building of more dams in the Sierras since the Stan, and no more rivers have been lost, at least so far. Yet, there is an active effort to raise the Shasta Dam which would intermittently flood Winnemem Wintu sacred sites, compromise the Wild and Scenic River status of the McCloud River, and further compromise salmon populations which are already at critically low levels. President Trump has supported adding $570 million Federal tax dollars to the federal deficit to fund this flawed project.

As the road twists and turns after leaving the reservoir I am reminded that I am drawing close to Sonora, which in the late 1970s was the location of Tuolumne County’s General Hospital. I began my career there as an Emergency Medicine Physician; working 24-hour shifts, solo, without the backup I enjoyed in big ERs in the city. Although some compare the experience to performing a high wire act without a safety net, I prefer to compare it to rowing Class V whitewater at big flows. When the going gets rough you need to quickly read the river, choose a route, and then stick to it. No matter how hopeless it seems you must keep pulling on the oars, and never give up. It also helps to have a Plan B, because your initial plan usually goes out the window after the first big hole or reversal. On Memorial Day over thirty years ago I had one of those Class V days at Tuolumne General Hospital in Sonora, and recalling it, I still get a shiver up my spine.

I had just finished the first year of my Residency at U. C. Davis, and being very green and perhaps more than a little stupid, I agreed to substitute for another more experienced physician who was too ill to work. No one told me the population of Tuolumne County doubles over the Memorial Day weekend as visitors rush to rivers, lakes, trails and the Yosemite Valley. Before my 24-hour shift was over I had seen several times the usual number of patients, and in the process the hospital set a series of records. There were several helicopter evacuations to Stanford’s spinal center in Santa Clara carrying my patients with unstable cervical vertebral fractures from diving accidents. This used up our supply of Crutchfield tongs, a spinal stabilization device I had never used before, and after reading the directions on the first set, by the third patient I was getting good at placing them. Then came a severe head injury from an autogyro helicopter blade that required a burr hole, a procedure usually requiring a CT scanner and a neurosurgeon, neither of which was available. I delivered a baby in the parking lot, intubated an asthmatic child with end stage respiratory failure which became complicated by a pneumothorax and required a chest tube, sewed up chainsaw lacerations until we had to send out for more suture, scrubbed out road rash embedded in Hells Angels until my own arms hurt, and between the sick kids and heart attacks, I was just barely keeping my head above water by afternoon. Then the tourist bus rolled over and the triage exercise began.

We call the ER ‘the pit’ for a number of reasons, and it is true that whatever doesn’t kill you in the pit can make you stronger. But what if it kills your patients? You cannot bring them back, no matter how sorry you may be they died. We need to wake up to the fact that it will be this way with our planet. What we do in the next few decades will be critical to the outcome. The future generations that judge us will know that we should have known better. After all, it was laid out for us over fifty years ago by scientists who have only been joined by more scientists, all sounding ever more dire warnings! We should have listened to Dr. Peter Raven, past President of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), who observed in the foreword to their publication AAAS Atlas of Population and Environment: “We have driven the rate of biological extinction, the permanent loss of species, up several hundred times beyond its historical levels, and are threatened with the loss of a majority of all species by the end of the 21st century.” How will we be remembered by those future generations? They may understand what triage means, and that we had to choose amongst the sick to help the survivable, but will they forgive us for being the cause of the sickness in the first place? I have asked myself whether that day in Sonora taught me lessons that would be useful in this future mankind is creating? Actually, I think it does, and this brings me to Evolution and Salmon.

As students of biology know, the process of evolution is the natural selection of genes based upon their fitness, that is, their production of characteristics that promote survival. It is a common misconception that evolution takes a long time, for instance, millions of years. Actually the time required depends on the selective pressure, if it is extreme the process of evolution can be very fast. Take, for example, the case of The Beak of the Finch as documented in the Pulitzer Prize winning book of the same title written by Johnathan Weiner. In this case the size and configuration of the beak of a subspecies of Darwin’s finches on the Galapagos Islands changed from sharp to blunt in a single generation. The reason was a severe drought, not unlike the ones we experience in California. The drought eliminated the plants producing the small seeds that the sharp beaked finches specialized in eating; leaving only a hard, large variety of seed only the blunt beaked finches could crack. Resultantly, all the sharp beaked finches died, leaving only the blunt beaked finches to reproduce. Interestingly, once the drought resolved and the various other types of seeds were again available, low frequency genes in the blunt beaked finch gene pool reasserted themselves and ultimately the sharp beaked finches dominated again. This illustrates the concept of a gene pool as a dynamic equilibrium, not a one-way street. It is also an argument in favor of genetic diversity. I think of it as a kind of genetic lifeboat, and similar to a lifeboat, you only fully appreciate its function when your ship sinks. These river canyons contain many such lifeboats. When these lifeboats are themselves in danger of disappearing they are referred to as ‘hotspots’. These are places where unique species and important genetic pools exist that are in danger of extinction.

Not long ago President Trump contended that in the face of California’s recurrent droughts it is wrong for our government “to choose fish over people” by using water to preserve salmon populations at the expense of agriculture. Actually, this misrepresents the situation, since people depend on salmon in a variety of ways, including food and jobs. The way I see it, the choice is actually between water for salmon versus water for the huge monocultures of nonnative species such as almonds and alfalfa that populate the Westlands Water District. These almond trees, it turns out, may soon need much more than just cheap water from the government. The National Climate Assessment, the Arctic and Antarctic ice sheet recession data, and the IPCC’s data on ocean acidification and temperature rise, all point to the fact that the effects of human induced climate change are being seen not in the future, but are here now. These changes are also surprisingly large and sudden.

One local example of such change is the disappearance of tule fog, and its relationship with almonds deserves exploring. It turns out almond trees require cold conditions to bloom, which in turn, has historically been produced in California’s Central Valley by that dense, cold, sometimes depressing stuff Valley folk call ‘tule fog’. A study by U. C. Davis scientists, which is based upon historical NASA weather satellite data, documents the rapid disappearance of the tule fog with an average decrease in the Central Valley as a whole by 46% over the last 32 years. In Sacramento itself the average decrease was from 223 hours per year to just 30 hours. Although this might be good if it only decreased the incidence of traffic accidents, if almond trees don’t bloom, there are no almonds. What are left are some of world’s most thirsty, yet barren, nut trees.

President Trump fails to mention in his fish versus people scold, that there are over 1400 dams in California and only one undammed river, the Smith. In fact, the vast system of hydrological plumbing that is currently in place already captures over 90% of California’s water runoff. The fact is, all the best dam sites were used decades ago. Since more dams will not produce more water, and since over 80% of the existing water is already allocated to agriculture, the wisdom of creating and maintaining vast monocultures of the world’s most water intensive nut tree should not be treated as sacred, but rather should be questioned. Which brings us to alfalfa for cows.

Granted, people need to eat. But did you know that 2 trillion gallons of California water is used to raise alfalfa and that 60% of this crop is exported to China, Japan and the United Arab Emirates to feed cows in those countries? Some of this beef is Kobe beef, a type of Wagyu beef raised in Hyogo Prefecture, Japan, and known for its flavor, tenderness and marbling. It is the most expensive in the world and available only to the most expensive restaurants. Similar to almonds, this exportation of California’s water occurs regardless of drought conditions.

Today mankind faces massive challenges. There are too many humans consuming too many resources to allow for a state of sustainable equilibrium. We know this, yet we seem unable to make the necessary changes to address the problem. It is often said that we as a species are destroying the planet Earth. Actually, I am more impressed that we are destroying what we like most about the planet, including salmon. When Dr. Raven says “a majority of species” he means this is an extinction event not unlike the Fifth Extinction that followed the impact of an asteroid in the Gulf of Mexico 65 million years ago. The difference is that the Sixth Extinction is not being imposed from space, but rather humans are choosing it. Whereas the Fifth Extinction took over a million years, the human caused Sixth Extinction may play out over only one hundred of years. If this seems improbable, consider that according to the World Wildlife Fund, wildlife populations have decreased on average over 70% since 1970. Faced with such threats it is time for humankind to carefully reflect and reorder our priorities. It makes sense to refrain from simplistic slogans that pose false choices, and, speaking metaphorically, to evolve culturally as a species. We need to become wise as well as powerful. After all, extinction is forever.

On the road,

Scott the River Doc